Like pretty much every print magazine, the venerable New Yorker has recently decided to rethink its online strategy, with a redesign and lots more online-only exclusive content. They’re also redoing their paywall, and before it goes back up this fall, you’ve got the rest of the summer to read anything from their archive — literally everything from 2007 to this week’s issue, plus plenty of older gems — totally free. Here are some recommendations of what New Yorker stories to add to your late-summer reading list. (P.S., if you like what you see, why not support independent long-form journalism and subscribe?)

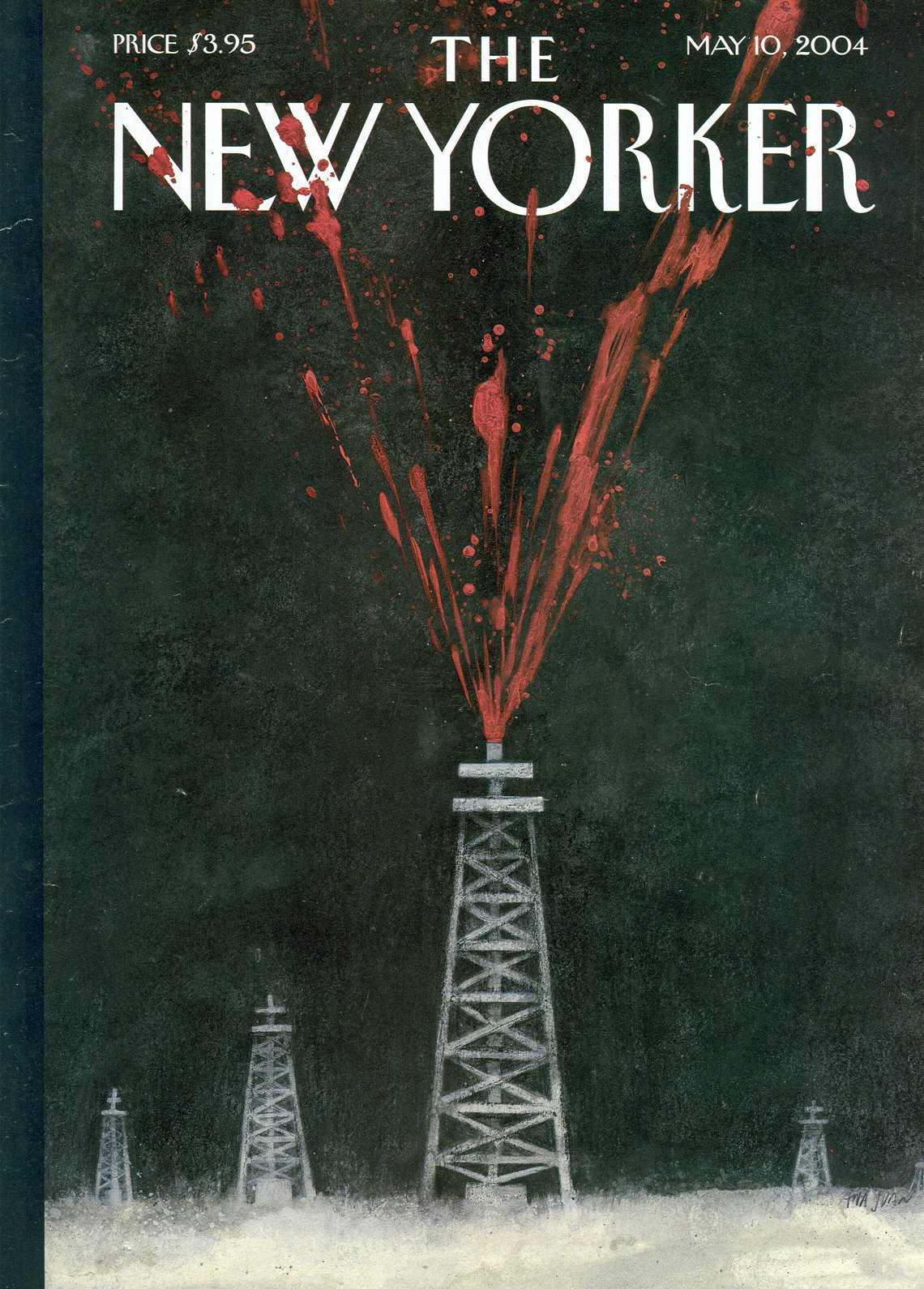

1.“Torture at Abu Ghraib,” Seymour Hersh (2004)

Myers, who was one of the military defense attorneys in the My Lai prosecutions of the nineteen-seventies, told me that his client’s defense will be that he was carrying out the orders of his superiors and, in particular, the directions of military intelligence. He said, “Do you really think a group of kids from rural Virginia decided to do this on their own? Decided that the best way to embarrass Arabs and make them talk was to have them walk around nude?”

If you don’t think this kind of magazine breaks news, think again. This deeply-reported piece helped turn the whispers that something was going very wrong in Iraqi prisons into an uproar, and showed as a lie the notion that the crimes that took place were simply the work of a few “bad apples.”

2. “Birdbrain,” Margaret Talbot (2008)

Pepperberg told me that Alex also made spontaneous remarks that were oddly appropriate. Once, when she rushed in the lab door, obviously harried, Alex said, “Calm down” — a phrase she had sometimes used with him. “What’s your problem?” he sometimes demanded of a flustered trainer. When training sessions dragged on, Alex would say, “Wanna go back” — to his cage. More creatively, he’d sometimes announce, “I’m gonna go away now,” and either turn his back to the person working with him or sidle as far away as he could get on his perch. “Say better,” he chided the younger parrots that Pepperberg began training along with him. “You be good, see you tomorrow, I love you,” he’d say when she left the lab each evening.

A must-read for animal lovers, Talbot closely follows the researcher most widely known for trying to understand how animals’ minds work, and takes readers on a tour through the history of smart (or “smart,” depending who you ask) creatures.

3. “Happy Feet,” Alexandra Jacobs (2009)

Unlike most Web sites, including Amazon’s, which seem to be operated by spectral forces rather than by human beings, Zappos prominently displays a toll-free customer-service phone number. There are no limits on call times, and the resulting sessions occasionally resemble protracted talk therapy. On July 5th, a twenty-two-year-old C.L.T. member named Britnee Brown, who has been with the company for a little more than a year, took a call that was a record five hours, twenty-five minutes, and thirty-one seconds long, from a woman on the East Coast interested in Masai Barefoot Technology shoes, which purport to mimic supposedly salubrious barefoot-on-the-beach walking with curved rubber platforms. “We started talking about her sister,” Brown said.

Stories that take the reader through the ins and outs of how businesses work are surprisingly common in the New Yorker. Perhaps what’s more surprising is how fascinating even the most pedestrian of operations turns out to be, and what these stories — like this one, about Zappos — tell us about the American psyche.

4. “Offensive Play,” Malcolm Gladwell (2009)

McKee is a longtime football fan. She is from Wisconsin. She had two statuettes of Brett Favre, the former Green Bay Packers quarterback, on her bookshelf. On the wall was a picture of a robust young man. It was McKee’s son — nineteen years old, six feet three. If he had a chance to join the N.F.L., I asked her, what would she advise him? “I’d say, ‘Don’t. Not if you want to have a life after football.'”

The epidemic of concussions and related diseases in football was just coming to light when Gladwell published this piece. Looking in unstinting (and upsetting) detail at football and dogfighting, Gladwell really forces you to think about what exactly it is you’re cheering for every Sunday.

5. “The Catastrophist,” Elizabeth Kolbert (2009)

“I had had hopes that Obama understood the reality of the issue and would seize the opportunity to marry the energy and climate and national-security issues and make a very strong program,” Hansen told me. “Maybe he still will, but I’m getting bad feelings about it.”

Kolbert’s consistent, solid reporting of horrific environmental disasters past and present is so important and eminently readable that it’s hard to choose just one story to highlight. The profile is a classic New Yorker style of story though, and her look at James Hansen — then a climate expert at NASA, now retired to pursue activism and teaching — now reads as an even more damning indictment of our continued inaction on climate change.

6. “The Cost Conundrum,” Atul Gawande (2009)

I gave the doctors around the table a scenario. A forty-year-old woman comes in with chest pain after a fight with her husband. An EKG is normal. The chest pain goes away. She has no family history of heart disease. What did McAllen doctors do fifteen years ago?

Send her home, they said. Maybe get a stress test to confirm that there’s no issue, but even that might be overkill.

And today? Today, the cardiologist said, she would get a stress test, an echocardiogram, a mobile Holter monitor, and maybe even a cardiac catheterization.

New Yorker contributor Dr. Atul Gawande also has a regular “beat” — the surgeon and public health researcher covers the field of medicine, often bringing in his own perspective as a practitioner. This examination of McAllen, Texas looks at a deceptively simple question — does more costly health care mean better care? — with a complicated answer.

7. “Standing By,” David Sedaris (2010)

Of course, you can’t just ask people whom they voted for. Sometimes you can tell by looking, but the grandmother with the many bracelets could have gone either way. In the end, I decided to walk the center line. “What gets me is that they couldn’t even spell ‘motherf-ker’ right,” I whispered. “I mean, what kind of example is that setting for our young people?”

Like many other writers who are also regular New Yorker contributors, material that winds up in Sedaris’ books often first sees print in the magazine. A master of dissecting the everyday and making even his most intensely personal experiences feel somehow universal, Sedaris is also a whiz at making anything — even air travel horror stories, as here — downright hilarious.

8. “Funny Like a Guy,” Tad Friend (2011)

“A month before the shoot,” Faris said, “they got me a gym membership and a trainer, which is standard.” She added, deadpan, that after she lost five pounds “they sent me a bouquet — and said, ‘Don’t eat it.'” During the filming, she subsisted on turkey slices and carrot sticks. “I felt they might have pulled the movie if we fought any further,” she said. “But it still bothers me: why would Ally be unemployed and wearing Prada shoes?”

If you’ve ever wondered how it can be that, as Paul Feig recently opined on Twitter, making a movie with women in the lead roles could still be a gimmick in 2014, read this profile of Anna Faris. It will leave you both darkly depressed about the state of gender politics in Hollywood and madly in love with Anna Faris.

9. “Netherland,” Rachel Aviv (2012)

Samantha and Ryan talked about the “housed world” as if it were an exotic culture, intrinsically superior to their own. They spoke in academic tones, trading theories about the patterns of “housed thinking.” They treated the subway, where they occasionally panhandled, as a human laboratory: people’s impulses toward charity had far less to do with them, they concluded, than with the other passengers riding the train. Few people looked at their faces until the first dollar changed hands, which then created some sort of force field — other passengers would suddenly feel compelled to be generous, too. They rode the trains deep into Brooklyn, because they found that poorer passengers were more likely to hand over their change.

Aviv follows the lives of a group of homeless LGBT youth in New York City, chronicling the improvised families that are created on the streets and the ways they stitch together lives on the fringes of society. This story will break your heart.

10. “Altered States,” Oliver Sacks (2012)

Within a minute or so, my attention was drawn to a sort of commotion on the sleeve of my dressing gown, which hung on the door. I gazed intently at this, and as I did so it resolved itself into a miniature but microscopically detailed battle scene. I could see silken tents of different colors, the largest of which was flying a royal pennant. There were gaily caparisoned horses, soldiers on horseback, their armor glinting in the sun, and men with longbows. I saw pipers with long silver pipes, raising these to their mouths, and then, very faintly, I heard their piping, too. I saw hundreds, thousands of men — two armies, two nations — preparing to do battle. I lost all sense of this being a spot on the sleeve of my dressing gown, or the fact that I was lying in bed, that I was in London, that it was 1965.

Many of Sacks’ essays about patients and others he’s encountered as a famed neuroscientist were published in the New Yorker before they made it into books. In this bit of “Personal History” — New Yorker-ese for memoir — Sacks turns the tables and recounts exploring his own mind via assorted controlled substances.

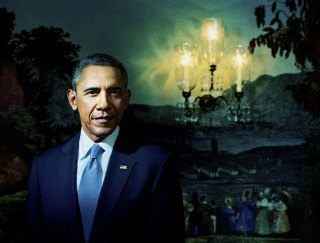

11. “Going the Distance,” David Remnick (2014)

“You have an economy,” Obama told me, “that is ruthlessly squeezing workers and imposing efficiencies that make our flat-screen TVs really cheap but also puts enormous downward pressure on wages and salaries. That’s making it more and more difficult not only for African-Americans or Latinos to get a foothold into the middle class but for everybody — large majorities of people — to get a foothold in the middle class or to feel secure there. You’ve got folks like Bob Putnam, who’s doing some really interesting studies indicating the degree to which some of those ‘pathologies’ that used to be attributed to the African-American community in particular — single-parent households, and drug abuse, and men dropping out of the labor force, and an underground economy — you’re now starting to see in larger numbers in white working-class communities as well, which would tend to vindicate what I think a lot of us always felt.”

The magazine’s editor in chief penned this extra-long, surprisingly candid profile of President Barack Obama. With a broad scope, the article gives a strong sense of a president finding his footing both in the present moment and in history.

12. “Here’s the Story,” David Gilbert (2014)

In Elysian Park, a growing line of people held hands and weaved through the crowd as fast as they could, the leader the needle guiding the thread. Bobby was somewhere in the middle. It had been too tempting for him to let pass without joining, and he had handed his mother the three balloons and jumped onto the end, holding this position briefly until others grabbed on and the line grew longer, its stitching more intricate. Emma watched from a distance. Every now and then, Bobby swung into view and she smiled and waved, feeling glad to be here, the strangest of Sunday picnics.

This taut, nostalgic short story begins with a bit of evidence — “this is what we know” — and then takes you on a trip through intersecting suburban lives. You won’t believe where it winds up.